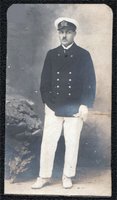

When you have had the benefit of a 25-year stint at sea (1959-1984), there is bound to be much that is narratable and shareable, with some of it even of interest to a few people outside your immediate family. But this post is, primarily, about Gupta Cha (and his family) - so I shall make only brief references to the other parts which will be covered in greater detail in "Ships and Shoes and Sealing Wax" (if that "book+" ever gets completed).

However, as indicated at the end of my previous post, the real conclusion to the tale - which took place last year - will make up the second half of this post. The first will be spent breezing through the intervening years.

When you have had the benefit of a 25-year stint at sea (1959-1984), there is bound to be much that is narratable and shareable, with some of it even of interest to a few people outside your immediate family. But this post is, primarily, about Gupta Cha (and his family) - so I shall make only brief references to the other parts which will be covered in greater detail in "Ships and Shoes and Sealing Wax" (if that "book+" ever gets completed).

However, as indicated at the end of my previous post, the real conclusion to the tale - which took place last year - will make up the second half of this post. The first will be spent breezing through the intervening years.

Ok, so it's 1947, the last day of September. Abi has finally received permission to extend his leave and proceed with the family to Karachi. We are to set sail on the S.S. DUMRA (of the British India Steam Navigation Co.) and are standing on a pier.

There's a mad rush wherever one casts an eye. If I had known of the concept

then, I would probably have thought of

Maedaané Hashr. The sounds of bawling from families being separated can be heard mingling with the shrill laughter of children running everywhere, excited by the journey.

The 5 of us soon board the ship, bidding goodbye to Gupta Cha and to Badshah Chacha, who has travelled from South India to see us off. Standing with them is a close friend of my father, the

amazing Dr. Baliga (one of my 'ideals' when I was a teenager), who was once invited to Pakistan to treat our Governor General, Ghulam Mohammad.

A couple of Sikh hockey players from the Bombay Sea Customs, 'fans' of Abbu Jan, have arrived to say goodbye to their Hockey Hero,

but now seem more interested in Chacha Jania (Talat Mahmood) whom they have cornered. As usual, he is too shy and polite to get away from them, though he wants to join us for parting hugs. The very moment that we start up the gangway, he runs towards us and the Sikhs shout out to all, "Yeh Talat Mahmood bhaaga jaa rahaa hae Pakistan. Roko. Roko." The laughs lighten the sad moment. \

We are shown to a cabin which, though meant for 2+1, is spacious enough and the bistarband comes in handy. Soon, the ship's ropes are cast off and we move gently away from the pier. The air is suddenly filled with wave after wave of loud roars of Pakistan Zindabad and Quaid-e-Azam Zindabad. One can feel not just the passion but the freedom in those naaraas, suppressed at the pier where everyone realized that such slogans could incite riots.

Once Bombay harbour begins to fade out of sight, Abi contacts the officer who is doing the rounds to inform him that he is a doctor and available for any emergency help that the ship's team might need. An hour or so later, he is called up by the captain and, with two other doctors and a couple of nurses also travelling as passengers. They are introduced to the Ship's Medical Officer and agree to do frequent rounds and assist with any passengers needing help.

At some late hour we are woken up by Abi to meet - and accommodate, if possible - a couple trying to find a comfortable place to rest. He has found them on his very first round. The bearded husband is none other than poet

Bahzaad Lakhnavi. Some of you may be familiar with Begum Akhtar's rendition of his

"Deevaana Banaana Hae To ..."

Once a r

angeen shaaer, Bahzaad Chacha later turned into a very prolific

naat go, and now lies buried in Karachi with signs on the graveyard proclaiming his

ishqé rasool. His unique

tarannum was extremely popular with

müshaerah audiences. The next 3 days of the journey are spent with him and Abi reciting

ghazals to each other with a slowly increasing 'fan club' blocking the passageways.

The day before arrival in Karachi is my 7th birthday. Bahzaad Chacha gives me a

shayr as gift. The original, in his hand, has long been lost ... but I still remember the words:

Tüm ko tohfay mayñ aur kyaa dayñ ham?

Lo nayaa mülk ... Iss mayñ phoolo phalo!

Abbu Jan gets a small temporary house somewhere near Jackson Bazaar in Keamari and, later, moves into the large Customs Flats nearby. We live with them for a few weeks while Abi - almost penniless - does the rounds in Karachi in the hope of finding a suitable job in some hospital. He does not wish to re-join the Army and has applied for release.

One day, quite by chance, Abi bumps into Swami Ji (as we always addressed him). He recognizes Abi as one of his fellow students at medical college. Abi learns that Swami Ji and two other colleagues run a charitable hospital - with free treatment for Hindus - under the Ramakrishna Mission.

They are on the verge of leaving for India, after handing over the place to GoP (as evacuee property, I guess). The stock of medicines, good for about a year, is to be thrown out since transferring them to other hospitals is considered a major task of logistics and accounting.

Abi is apalled. He says he would like to continue running the hospital, without charging the Mission, until all the medicines run out. He promises to keep it free for Hindus if the Mission agrees that the free treatment could also be extended to Muslim refugees who cannot afford to pay. They agree, but there is the Government to convince. Abi's old Aligarian friend, Mr A. T. Naqvi, now the Commissioner of Karachi, arranges for this to be formalized and, suddenly, Abi has a job which, though it carries no salary, comes - to our delightful surprise - with a small 2 room apartment on Nazareth Road (half-way between Guru Mandir and Soldier's Bazaar). We live next to the larger apartment occupied by Swami Ji and his colleagues. I am in and out of their house all day, devouring all the

Idlees and

Dossas and

Rasm they can feed me - which explains my desire to dart off to the South Indian

Sagar restaurant the moment I get to Dilli. (If you ever go there, be sure to try their almost-3-foot-long Paper Dossa.)

Diversion The Nazareth Road house is purchased the following year by a Nawab Hasan Yar Jang (nephew of the colourful Nizam of Hyderabad) and Swami Ji manages to have it written into the agreement that as long as Abi is alive he can continue to stay in that apartment, paying rent - of course. The Swamis leave in a few months. Nawab Sahab - always very civil when we encounter him in the building - shifts in with his 'lingerers on'. He gives me my favourite mithai - genuine Baadaam Ki Lauz - whenever he receives a package of it from Hyderabad. I even get to go with him and (What a treat!) sit in the Royal Stall to attend the Platinum Jubilee of Aga Khan III (grandfather of the present one), a ceremony Nawab Sahab is attending on behalf of the Nizam.

But Nawab Sahab is a stickler for words. The contract says that my father can occupy the house as long as he lives. On 18th September 1963 my ship happens to arrive in Karachi.  On the 19th my father dies. (Abbu Jan and Ammi Jan are getting a house built in Iqbal Town and are temporarily staying with us, which offers Ummi and me a bit of solace, since we have all been very close, always.) The Nawab attends the funeral, comes into the house to condole with my mother, and informs me on his way out that we have to vacate the house in 48 hours! Which is what I try to do, but it takes a bit longer and needs the good offices of neighbour, ex-Mayor Khan Bahadur Gabol Sahab, to convince the Nawab. I sail away two days after our hurried shifting. This trip to Karachi has been a life-changing experience for someone only 23 years old. But let me get back on track.

On the 19th my father dies. (Abbu Jan and Ammi Jan are getting a house built in Iqbal Town and are temporarily staying with us, which offers Ummi and me a bit of solace, since we have all been very close, always.) The Nawab attends the funeral, comes into the house to condole with my mother, and informs me on his way out that we have to vacate the house in 48 hours! Which is what I try to do, but it takes a bit longer and needs the good offices of neighbour, ex-Mayor Khan Bahadur Gabol Sahab, to convince the Nawab. I sail away two days after our hurried shifting. This trip to Karachi has been a life-changing experience for someone only 23 years old. But let me get back on track.

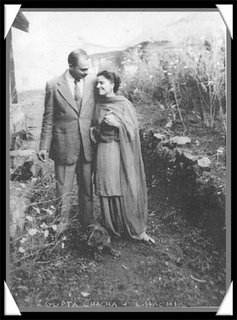

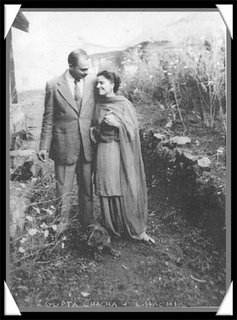

Gupta Cha is in touch by mail and we receive a picture of him and Chachi soon after their wedding in 1949 or 1950.

This exchange continues, off and on. When Abi dies, Ummi receives a very warm letter from them, asking "Bhabiji" to stay with them in Dilli for a while. But the trip never materializes. We couldn't afford it. Then, for some reason - possibly mail going astray after the 1965 war - we all lose touch.

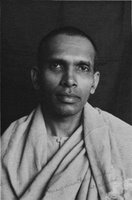

For years I search for him ... but can recall neither his rank nor

anything else. Whenever my ship is at an Indian port, I try to think up ways to find Gupta Cha. Trying to find a 'Gupta' in the Indian army, I am told, is just short of tracing the right 'Khan' in Afghanistan.

Zoom ahead to 1983: I am in command of a ship operated by the Gokals out of Hong Kong. The officers and crew of these ships are multinational and on my ship the Chief Engineer, Vipin Kaura, is from India. Vipin's father - a retired Army officer - comes from Dilli to visit our ship and stays there for a few days.

Soon after 'Uncle Kaura' arrives, I decide to go wish him. I plan to remember to say Aadaab in the old tradition but my Pakistani Radio Officer - a Lahori - tells me that that was not as common a greeting in Punjab as in Delhi and the U.P., so maybe I should say Namsté to be polite. I walk in and say that, a bit awkwardly, failing badly at the hand coordination for the accompanying gesture. Uncle Kaura - originally from Rawalpindi - says. "Aray ... hum to soach rahay thay keh bohat din baad Salaam Alaeküm sünnay ko milay ga ..." and soon the talk turns to his homesickness and losing touch with old friends. He regrets forgetting to write Urdu well.

During the stay I recount 'our' partition story and he asks me if there is anything I can recall about Gupta Cha that could help trace him. Apart from his first name, Birjesh, I usually can't recall anything. But from some hidden corner of my mind, that day, I bring forth two facts that I'd never consciously recalled earlier. Someone in Gupta Cha's family - possibly his father? - was a Judge. And they lived in a house called

Bürj Mahal in Meerut. Before he leaves the ship and heads home, Uncle Kaura says he will ask some old colleagues about Gupta Cha but doubts if anything will come of it.

Five days later, I am standing at the Shipping Agency office when I am handed an envelope posted from Delhi, addressed to me. I open it and discover a letter in Urdu in a shaky hand. It starts "Pyaaray Baytay ...". "How sweet of Uncle Kaura," I think to myself, "to try and write in Urdu after all these years." But the next para that I read

(writing this I am still feeling the same sensation as I did then) is something I cannot believe. I jump ahead and look at the bottom of the next page. YESSSSS! It says "Tümhaara Gupta Cha". It takes me an interminable amount of time to absorb this. A clerk comes up and asks if I am OK. I have tears streaming down my cheeks and can barely speak as I read about Gupta Cha thinking each year of me on my birthday, admittedly not difficult to remember in India (It's Gandhi Ji's, too!). I read and re-read the letter. He wants me to fly out to Delhi. Of course I cannot (not just because of the visa but because we sail out in 2 days).

It turns out that Uncle Kaura, immediately on his return to Delhi, took a bus to Meerut and spent the day searching for Bürj Mahal. Unsuccesful at his attempt, he stopped at a shop in a multistory building to have a cold drink before taking the bus back. The shopkeeper and he got into a conversation and he mentioned his search for Bürj Mahal. "This very building is where it used to be," said the shopkeeper, "and the old owners live right on top, I think." So up climbed Uncle Kaura and met Gupta Cha's sister-in-law and told her the tale. She recalled our family and informed Uncle Kaura that Gupta Cha lived in Delhi! Defence Colony!! One lane behind Uncle Kaura's house!!! (Yes, Woody Allen. Life does imitate bad television!). So it is to Uncle Kaura that I owe more than I had realized.

After I regain control of my senses (and I am not dramatizing this ... it

did take a while, as 36 years and all that's happened in that period ran through my mind) I immediately decide to phone him. And Ummi. Getting connected to Karachi, oddly, happens very quickly but I just manage to tell her that I've found Gupta Cha when, even more quickly, the line drops and we cannot get through again. Getting through to Delhi is a 'trunk call' - as calls between cities were then known - and requires a 'booking'. "It's about a 3-4 hour wait," says the operator. The manager of the agency, who, like everyone else in that room, has heard bits of my story by then, takes the phone from me and says something in Marathi, and then translates it for me.

"Maeñ saalay ko bola 'Yeh jaldi type ka call hae! Death and Illness Emergency'. Abhee das minat mayñ mil jaae ga."

Of course I can't recall the conversation with Gupta Cha. Too full of both of us trying to fill the other in about everyone and everything. Sobs. Laughter. He tells me he has two children. The son, nicknamed 'T2' is in the army. His daughter, Nanu, is married to Sunil who is in the Navy and is posted in Bombay. I am excited. "Can I see her?" Gupta Cha gives me the address of her house in the Naval Colony and, still reeling from all this, I am put on a rickshaw by the friendly clerk who first tells the driver my story and then instructs him to wait wherever I am going and bring me back later and collect the money from the office as part of the celebrations for my joy. Awwwww.

So off I go. Kinda stupidly quick response, if I'd just thought a bit. I can't even get into the Naval Colony in my own city without some identity papers. And, as a Ship Captain from Pakistan, I should not even be near an Indian Navy area. But who was thinking? In retrospect, I often shudder. Had I been arrested and charged with a Pak spy masquerading as an Indian, I'd still be in jail there, if alive. But I was not pretending about anything. I was excited and that's all that must have shown on my face. No nervousness at all. Just a stupid pasted smile of the kind that airline staff bear. The clothes, too, helped. I was in a white

khaddar kurta pyjama - my usual dress code for the evenings - a common sight in Bombay, anyway. The chatty rickshaw vaala, who informed me that he was a Muslim and had relatives in Karachi, spoke to the guard when he asked where we were headed. "Aray chho∂o yaar ... 30 saal baad behen say milnay jaa rahaa hae sahab!" And we were in.

Later, I have laughed often at the thought that the Indian Naval Security services are at the same level as ours - recalling that in the 60s, when we docked in Karachi with ammunition that our ship had brought in from Iran, the whole port area was under security and passes were required to board the craft. Not even our own officers could step onto the quay and board the ship again without passes. Sitting in my room, I nearly leapt out of my chair as I saw an old friend from India walk in. "How the eff did you get on board? It's bloody tight security!" ... Bhagwan Das winked and said, "Full Paanch rupyah diya gate vaalay ko, yaar!"

The meeting with Sunil and Nanu was great. It was like being at home with people I'd always known. No takallüf.

They already knew of me. Their elder daughter, Ayeshah, (named by Gupta Cha) fell asleep soon but I did get to carry around the new addition, 4-month old Amrita, after eating a lovely home-cooked meal, so that Nanu could eat in peace. I wish the ship would have stayed longer so I'd have got to spend more time with them.

For a year or so Nanu and I managed to stay in occasional contact, but Sunil was then posted to Vishikhapatnam, I think, and none my letters ever reached them, so we lost touch.

Gupta Cha and I wrote to each other often and I phoned him from several ports - Hong Kong, Singapore, from wherever I could dial direct. He and Ummi, too, exchanged a few letters (in Urdu!). He was insistent that I hop across the border and stay with him for a few days. "I have a room reserved for you", he'd always tell me. But visas were an impossibility for me then.

I returned to Karachi in late March 1986 and Ummi told me that Gupta Cha had passed away just a couple of days earlier. Fate's cruel joke... to have found him after years and never met him! I spoke to Chachi on the phone. There was less to say except in silence.

Some time later, I received a call from "T2", whom I had not been in any kind of contact with. His addressing me as "Bhaisaahab" seemed so strange.

He told me they were letting go of the house and he was taking Chachi along to wherever he was posted then. Chachi came on the line - and in one of the most touching moments for me in this strange saga - asked me if it would be possible, before they left the house, to come and stay a day or two in the room that Gupta Cha had earmarked for me. I tried but I could not get the NOC needed for a visa. (Although I had left the sea - swallowing the anchor soon after my daughter's birth … and Ummi's accident that confined her to a wheelchair … and started a company of my own, my passport still showed Merchant Seaman as my profession, so our Ministry had to issue NOCs.)

I never managed to contact T2 and Nanu again. Uncle Kaura, too, passed away before I could find out the address from where, maybe, I could get a forwarding address they'd left behind.

On my next trip to Delhi, much later, I told Vipin about trying to find T2 and, together, we called up several Guptas, none of whom could help. I discussed with Tarun (of Tehelka) the possibility of an ad in his paper looking for these people but we never got around to it.

Fast Forward: It's late 2007. I am sitting at T2F in Karachi and get a call from a Pakistani Merchant Ship Captain, some years junior to me. We don't really know each other. He is writing a book about our Merchant Navy and wants any photos that I may have which could be used. Then he says, "I was in Bombay last week at a meeting and there was someone who wanted to get in touch with you. I promised to trace your numbers and send them to him." I imagine it's one of my many Indian fellow seafarers from the NOL (Singapore) or GESL (Hong Kong) days. But it turns out that it's someone from the Indian Navy.

"SUNIL?" I almost shout the question. "Yes."

It's just too crazy! I get Sunil's number and call him up. Later, I speak with Nanu. I learn that Chachi is no more. None of us ever got to meet her

:-( Then I get a Delhi number and call T2, whom I'd searched for as a Major? Colonel? Something Gupta. In all the years I was in contact with the Gupta family, no one had ever mentioned T2's full name! Turns out he is Pradeep Kumar.

Chalo. And he's been living in Delhi for a few years (during many of which I've been visiting the place often, even for long periods).

Much as I wanted to, I could not attend T2's son (and my fellow Merchant Navy Officer) Abhimanyu's wedding in Jaipur, where Ashmita's family live.

Just a few days earlier that city had suffered from bomb blasts (obviously, the blame was laid at

our doorstep, as is customary) so getting a visa to that city was out of the question.

Things are getting better. T2 met our daughter in Dhaka during his business trip. I met him and his wife, Ruby, when I stopped over in Delhi en route to Kolkota for a meeting. Sunil flew over from Mumbai and we had dinner together. Nanu, I hope, will be able to come to Delhi the next time I am there (hopefully in the last week of the next month). And I am dying to see the kids all grown up.

If ever there could be a suitable postscript to all this, it's this email I received just a while ago.

If ever there could be a suitable postscript to all this, it's this email I received just a while ago.

Peace!

Labels: Books, Events, Music, Pakistan, People, Personal, Poetry

In the beginning, I would get very defensive with Sukhendu whenever something like the BJP used to come up in conversations but then I was reminded of a story that I think has largely shaped my thinking. At school I learnt from textbooks that one Rashid Minhas was the recipient of the Nishaan-e-Haider and a brave and valiant soldier who had grappled with the Bengali flight Instructor, Flight Lietenant Matiur Rahman who was a traitor. I grew up hero worshipping Minhas. When I came back to Bangladesh, I was shocked to learn that for the Bengalis it was Matiur Rahman who was the hero and not Rashid Minhas, who they considered the enemy. I realized then that the history of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh is so intertwined and so full of passion and extraordinary circumstances that it is impossible to take sides. Both men as I see it today were heroes and valiant soldiers who just happened to be on opposite sides of the cause. It was an accident of birth. This realization has, on one side, liberated me and, on the other side, saddened me beyond imagination. This means that we will always be at each other's throats and no one will see the person but only the flag that he is wrapped in. Of course I am exagerating, but I am telling my story fully for the first time. I think you will understand the confusing identities that I live with and also that there will always be people who will rise above pettiness :-) Thanks for listening to me. God bless! Sarah ==================== Dear Sarah Wow! And you want me to write [down] my stories? Blog this just the way you've written it to me. At the moment it's a request but can be used as threat by saying I'll publish it on my blog ;-) It's real tales such as yours that will ensure that the only things we all really need to burn is not each other's flags but our own if peace is what we want. All the best. Zaheer PS: I hope you won't be offended at my saying this, but as an anti-nationalist, I would not accept that both RM & MR were heroes. They were just simpletons, brain-washed into committing such acts. But that, of course, pre-supposes that the story, itself, is true. There are some in the Air Force[s] who have, since, cast doubts on the veracity of the entire tale and think it was a crash that the PR-minded in Pakistan decided to use to advantage and the BD people, naturally, made the best of it. Who knows. So it goes ... ====================