Huzoor Abba

======

Memories play all sorts of tricks and, often, many of them may not be 'real'. Some are changed around by hearing things differently from different people. Others have little fluffments added on for pleasure. Or dread. My memories of Huzoor Abba, Safdar Ali - my paternal grandfather, have no such transformations that I could consider. They are few, but come straight from the actual days I spent with him.

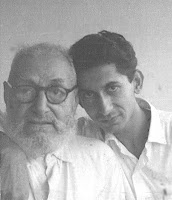

I hated most of them, I admit, though this old pic of him and me, taken a few days before his death, may not convey that.

HA was a strange man. Slightly to the right of Ivan the Terrible? I dunno. That's what my cousins and I used to call him when we were kids. We hardly saw anyone really speaking to him, other than an uncle or my khaala (who was also his younger brother's wife). Most people I knew of were afraid to be near him, other than as younger relatives categorically asking him how he was, or some such thing, and then disappearing fast.

My father was very fond of HA … for reasons that I've never understood. But it seemed that Abi was fond of everyone, so I guess that's the way he was. In fact, when I once said I was very upset at the way HA had treated him (specially having 'forgotten' him after sending him off to UK and not paying for his fees or anything), I was told that that was between him and his father and that I had no right to pass judgement over it. What a strange world that generation was.

My father was very fond of HA … for reasons that I've never understood. But it seemed that Abi was fond of everyone, so I guess that's the way he was. In fact, when I once said I was very upset at the way HA had treated him (specially having 'forgotten' him after sending him off to UK and not paying for his fees or anything), I was told that that was between him and his father and that I had no right to pass judgement over it. What a strange world that generation was.My own memories of him were rude, crude, distrusting, awful. He had not even the slightest aeon that he could spare for something that was not entirely in line with his thought. His anger and attitude - and there were many instances that I can recall - was something that really amazed everyone. Two that I can quickly recollect are from Calcutta:

1. His having locked me up, when I was just under 4, with his great big Alsatian in a small kothri just because I seemed scared. No lights. The dog barking away. My mother, in tears, in another room. Me crying out loud. My cousins - a couple of years older than I - writhing away in pain. I fell asleep. The dog, fell asleep, too, I guess. My khaala came later and fought with HA and pulled me out. He thought I'd gotten rid of my dog-phobia but it actually took years for me to overcome this.

2. Much worse, this was only a few days later. It was Eed. We were in my Khaala's house. I had these lovely shoes. You know … the ones with silver and red. Üff. How much fun they were. So I walked up to him, with Ummi, and told him that they were great. He looked at Ummi and said "Tüm ghar jaao. Zaheer ko maéñ lay kar aaooñgaa." I dunno what happened next. I do remember playing with my cousins who were there, too. And then he came up to me and said, "Jootay ütaaro!" … in an accent that there is no way I can write about. But it was fierce. I took off the shoes. "Socks", he said. They were gone. He caught me by the hand and, in the grossiest afternoon, at 3 o'clock, he made me walk barefoot, from his house to my khaala's. Two miles. My feet were killing me. I was blistering and in tears. People looked at us. We reached home. In the time that I was on the road and the few minutes I was at my house my feet were now burning. He said to Ummi: Bachchoñ ko ameer naheeñ banaatay. And left.

A doctor was called in. He was a friend of my father and it took a long time for my Khalu, Asad Ali, to convince him not to report it to the police. The doctor wanted my grandfather arrested. I was in bed for 4 days with bandages. I hated HA. Really hated him.Son of Munshi "Abr" Kidvai (who was the brother of Shauq - a classical Urdu poet), he and his 4 other brothers were fairly well-off as kids. He was a friend of the little Nawab sahab - since his father was a Munshi Ji in the court and much respected - and spent his childhood there, learning the ways of an elitist crowd, enjoying all the wonderful things that mattered in court (but not in real life), and having a great time. He studied at Aligarh University and was one of the earlier batch of students. He became a good engineer - many of his works are in Bombay (Mumbai!) or Calcutta (Kolkutta!) - but his great love was always the thrill of the courts and the charms of money and riches.

Being a friend of the little Nawab meant that he also rose, in time, as the Nawab became the head of the state. He became their Minister, or whatever that was called, of Forests and Architecture.

Being a friend of the little Nawab meant that he also rose, in time, as the Nawab became the head of the state. He became their Minister, or whatever that was called, of Forests and Architecture.His life remained that of a friend in court and, though he was now married (to a first cousin), his desires were way too close to those that the court found wonderful. Women were his folly - though I am told (and see from some pictures and a few writings) that his 'companies' (to use the word my chacha used) were great. But that's money. Not taste.

They lived in a large haveli in the state - in a house that seems almost impossible to think of today. Beautiful lake. Tons of trees. Wonderful place. Horses and cars were his favourite sports so there were those, too. Wrestling was another task he loved and there was a freestyle wrestler on the premises to teach him and the kids how to fight.

His youngest daughter, Bilquis, who died when she was 16 (the pic is taken a month or so before her death), was also a great person from what I hear of her. She loved riding, as did all the cousins who came to be in that house. Two brother's sons/daughters and hordes of other cousins who came from everywhere to visit just stayed on.

Then came a little problem. Nawab sahab fell in love with a brilliant singer and wanted to marry her. He was thrilled at her being 'a virgin'. HA advised him against it. There were little quarrels. Then it became worse. Finally, HA could not contain himself any longer and told Nawab sahab that he had been with this woman for months and that she was not a virgin.

Oooops. Not quite the thing you are supposed to say. And certainly not in public.

There were many in the courts who had hated HA for his close friendship and they thought the best way was to get rid of him. So they planned with Nawab sahab who, rather suddenly, sent out a bunch of staff to arrest and place HA into prison for 'having taken a bribe'.

HA's father went to the Nawab and said this was untrue. He was told what the problem was and he pleaded that his son not be accused of a false charge. Nawab sahab finally agreed — but with heavy demands. A contingent was sent to the house and everyone was allowed to be put into cars and taken to Lucknow. Every bit of jewellery, funds, utilities, silver - anything that had a value on it - were taken away. HA's hands were tied down - with his silk handkerchief - as a way of seeing him brandished as thief. That was the end of HA and his amazing days there.

In Lucknow the family gathered initially into Shauq sahab's house. (Some say that Shauq sahab had said, "Now that Safdar is here, we will have more problems.") - but not too much really happened that was as bad as this. Well, kind of.

The family was asked to get together and the brothers were told to sign away their properties in Jiggaur and the family sold them all so that HA would have the money to go out and set up an engineering firm. He did do that - but first having spent almost half of the money to buy a car! He drove from Lucknow to Bombay with it - passing as many train stations where he could pick up petrol that was shipped to him. Jeezus! On the way he stopped at many goras and other afficianados where he had a jolly good time and made friends - and acquaintances. That's how, in Bombay, he managed to get contracts.

The car? Well, two days into Bombay and he went to see a dancing girl. Loved the song. Gave her the car!!! (I had always heard this from everyone but could never figure it out. So, a few days before his death in Dhaka, I asked him. This is what he said: "You think classical music is great. And yet you can't understand how important it must be if you cannot figure out my giving a car for a really well-sung ghazal?")

I also asked him about the money his brothers had given him. Apparently, despite his own priorities, he said he did well and paid regularly back to his wife everything he thought was possible. (She was quite a gorgeous lady, as you can see in the image.)

I also asked him about the money his brothers had given him. Apparently, despite his own priorities, he said he did well and paid regularly back to his wife everything he thought was possible. (She was quite a gorgeous lady, as you can see in the image.)It was certainly enough for her to keep the rest of the brothers-in-law, nephews, nieces, a brother and his children, and several long distance cousins in the house. On top of that, she also had the house running like crazy - parties, classical music, friends (including Attiya Faizi, after whom Dadi named Attiya Habibullah - the one we all idolized as Baji Jania). Talat Mahmood was her brother's son and was taught to sing by her. She died in the mid 30s, of cancer.

My father and his brother - much apart in their own ways - were also far from their father's methods. My father, I have written about earlier. Chacha, I am told, was an affectionate man.

(I can only recall chacha in Calcutta, where he appeared for a visit soon after his wife died. Very little remains of him in my mind though I have heard a lot about him and have a selection of his ghazals that a friend from Rangoon sent us).

He stayed for 5 months at our house and, during those days, taught me Mathematics like magic - moving from one concept to the next that had nothing to do with what the books said. From getting 2/25 in month one, I was getting 20/25 in 4 months. Since then, I loved Maths and went on to score full marks in my Senior Cambridge (and did well in everything mathematical at sea).

Despite all this, the hate never really came to an end. He did everything - apart from teaching - to make sure that his anger remained the most important thing for me and the cousins who were part of our lives.

He went back and worked … but was not in anyway capable of looking after himself as time went by. Life was running out. All the money was gone. He lived in a small flat with nothing of any value. He sold stuff. My father sent some money, but very little - given our own bad shapes.

His eldest son died in Rangoon in 1952. My father died in 1963. HA had no 'real' feelings, as far as I could tell. All he had were old kurtas and a few tahmads that he thought were comfortable. And a bed that had every kind of engineering attachment that made it possible for him to do things without getting off, if possible. He lay down all day and read tons of 'cowboy' books.

I went to see him, when my ship was in Chittagong, and he seemed quite happy in that flat. He was lying in bed - smoking a cheroot - and I asked him if he didn't miss all the things he'd possessed. He said, "Only my lighter. These matches are a problem."